If you’ve ever watched the news, checked a weather forecast, or glanced at a climate meme, you’ve most likely seen the term “Indian Summer” used to describe a warm weather period that generally occurs after the first frost.

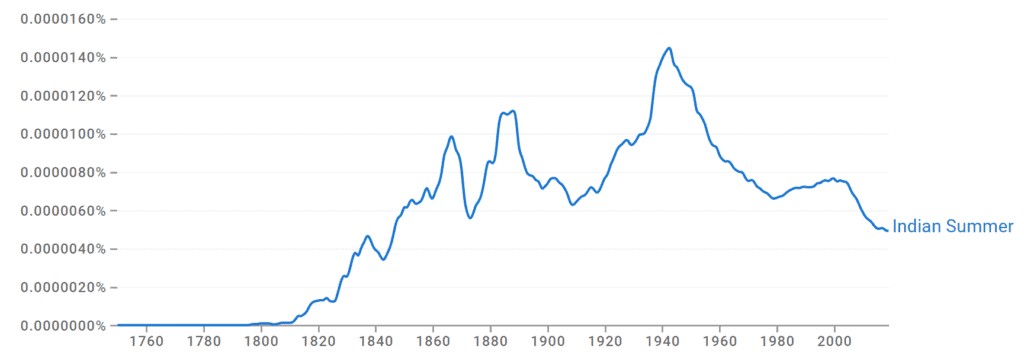

Despite the description being used less in the last few years, it has an interesting history that provides a nod to the Native American practices of harvest and food storage outside the draining heat of late summer.

Let’s take a closer look at its origin and use below.

What Does Indian Summer Mean?

The term “Indian Summer” is used in North America and Britain and describes a warming weather phenomenon that occurs during the autumn months. It can last anywhere between seven days or a few weeks and generally falls between late September and November, depending on regional climates.

It also can happen more than once during this time frame.

Even though there is no true definition, to be considered a true “Indian Summer,” it needs to meet the following accepted criteria:

- Warm spells must occur after the first frost and before the first snowfall.

- It must occur after the fall equinox (usually September 22nd or 23rd).

- Daytime temperatures must stay above 70 degrees Fahrenheit for at least seven days.

During this time, the days are also marked by an overall hazy autumn air caused by the sun being lower in the sky; crisp, cool, and clear nights; and a period of little to no breeze.

Indian Summer Origin

The first known published use of the term “Indian Summer” occurred in 1778 when referred to as such by Michel-Guillaume-Jean de Crèvecoeur, a French-American farmer, naturalist, and author.

It is widely accepted that he is not the originator of the term but that it had been used throughout temperate New England to describe a noticeable cyclic weather pattern that occurred almost every autumn as a precursor to the first snowfall.

Like many other terms from the time period, it was most likely influenced by the Native American tribes who were familiar with weather patterns to prepare for winter. Many of these lessons were taken advantage of by early settlers to gather the bulk of their vine-ripened harvest for winter storage, and fields were thrashed to ready for spring plowing.

Why Is It Called Indian Summer?

The early American settlers owed much of their survival to the lessons they learned from the Native tribes, especially concerning crop and animal husbandry production. It is strongly theorized that colonists took to calling this time period an “Indian Summer” because the Native tribes took advantage of it to shore up their winter stores, bring in the frost-hardy crops, and finalize the winterization of their dwellings.

This was likely due to many native plant species needing the extra bit of growing season to completely mature, such as various squashes and corn that can survive cool autumnal weather and frosts. Plus, late summer in these regions can be extremely hot and humid, making heavy harvests time-consuming and exhausting.

Colonists would have naturally used these lessons to extend their own preparations and ready themselves for what was often harsh, cold, and snowy winter weather.

Other Names for Indian Summer

The term “Indian Summer” is considered outdated for various reasons and has been used less and less in recent years. Although you will still hear it said and now know what it refers to, it is important to recognize what else it is called.

The American Meteorological Society will often refer to it as “Second Summer” since the name is very descriptive of the event.

Europeans and the British sometimes call it “Saint Martin’s Summer,” a reference to Saint Martin’s Day, which falls on November 11. England also uses the “Old Wives’ Summer,” “Halcyon Days,” and even provides a nod to their favorite bard, Shakespeare, who called the warmer patch of weather an “All-Hallown Summer.”

Let’s Review

Indian Summer is a period of warm fall weather that falls between the first frost and the first snowfall. It is defined by sunny, clear days; cool, crisp nights; a lack of wind; and temperatures above 70 degrees Fahrenheit during the day. It is also often associated with hazy weather as well.

The most widely accepted history behind the name is given to the Native American practice of finalizing the harvest and reading for winter, which was likely observed by early settlers.