Though plateau comes from French, the word has been in English for several centuries, and it is now an English word when English speakers use it, so we are free to pluralize it in the English manner—making plateaus. The French plural, plateaux isn’t incorrect, and some people like it, but its use is unnecessary in contexts where the word’s French origins are unimportant.

The matter is especially well settled in American, Canadian, Australian, and New Zealand English, where plateaux appears only rarely. In British English, though, the French form is only slightly less common than the English one. We can’t explain why this is, but it’s worth noting that the noun plateau in all its forms is far less common in British English than in other English varieties. This is obviously because the geological features known as plateaus are more prominent in Australia and the Americas than in the British Isles. Perhaps in British English the word is just not useful enough to have been fully Anglicized.

Incidentally, plateaux is pronounced the same as plateau because the x is (usually) silent in French.

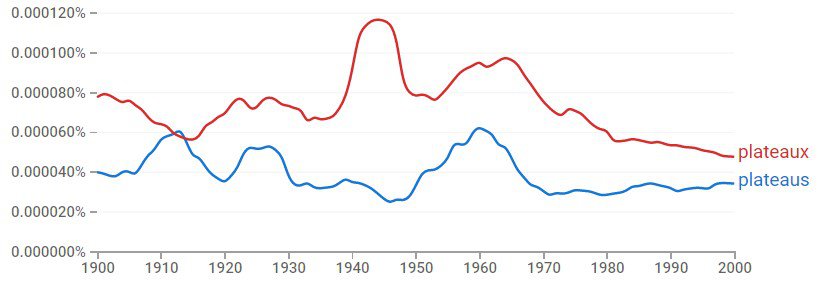

This ngram graphs the use of plateaux and plateaus in British books published in the 20th century:

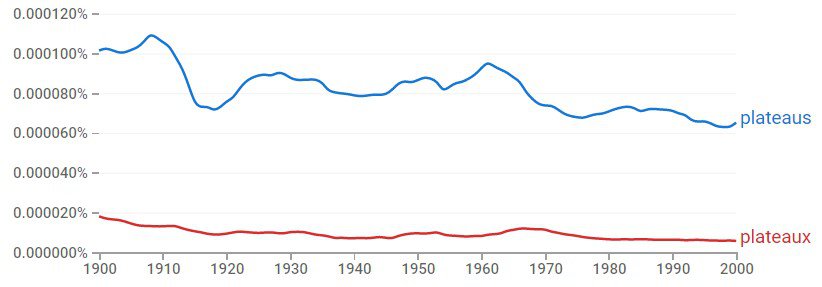

American use of the words, as shown in the below ngram, has been more consistent:

Examples

Though plateaux is difficult to find in publications from North America, Australia, and New Zealand, examples are more common British publications:

The viaduct spans almost 1.5 miles between two plateaux in the Massif Central. [Telegraph]

Ma writes brilliantly of the profound solitariness of Tibet’s remote desert regions and mountainous plateaux. [Independent]

By November swirling snow will have descended on the mountains, sealing off many of the valleys and high plateaux. [Guardian]

Comments are closed.